By David Katz

Three recent events I attended have helped drive home the message that it’s time to move to the next level of building – having more structures meet the smart grid and be sustainable.

And that means taking a sustainable approach which requires a life-cycle evaluation of all the options; from aesthetics, to environmental, to smart grid integration benefits.

The three events that had the issue of energy as major themes were about Building Integrated Photovoltaics (BIPV), Building Envelope Solutions (BES) and Smart Grid Canada (SGC).

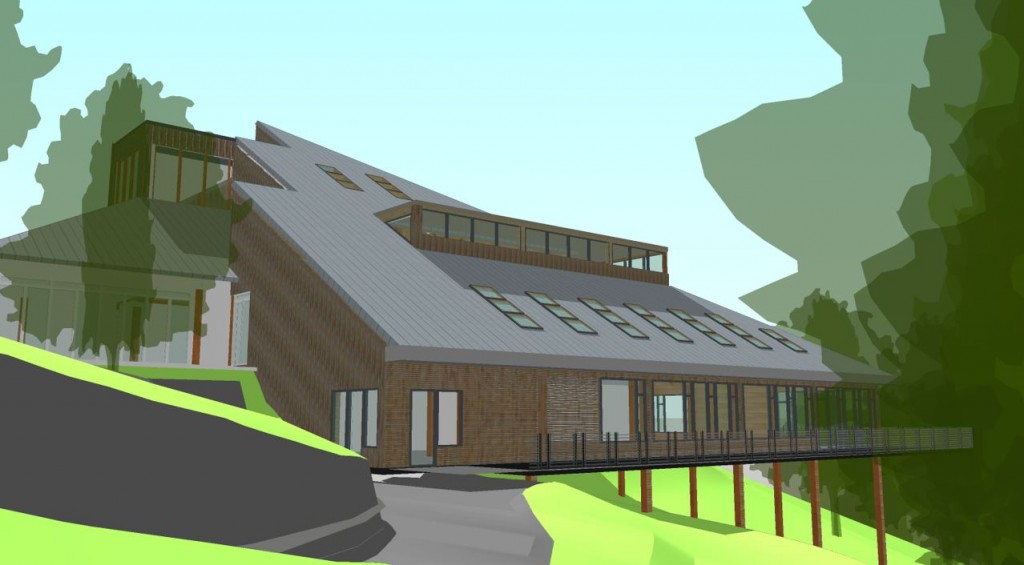

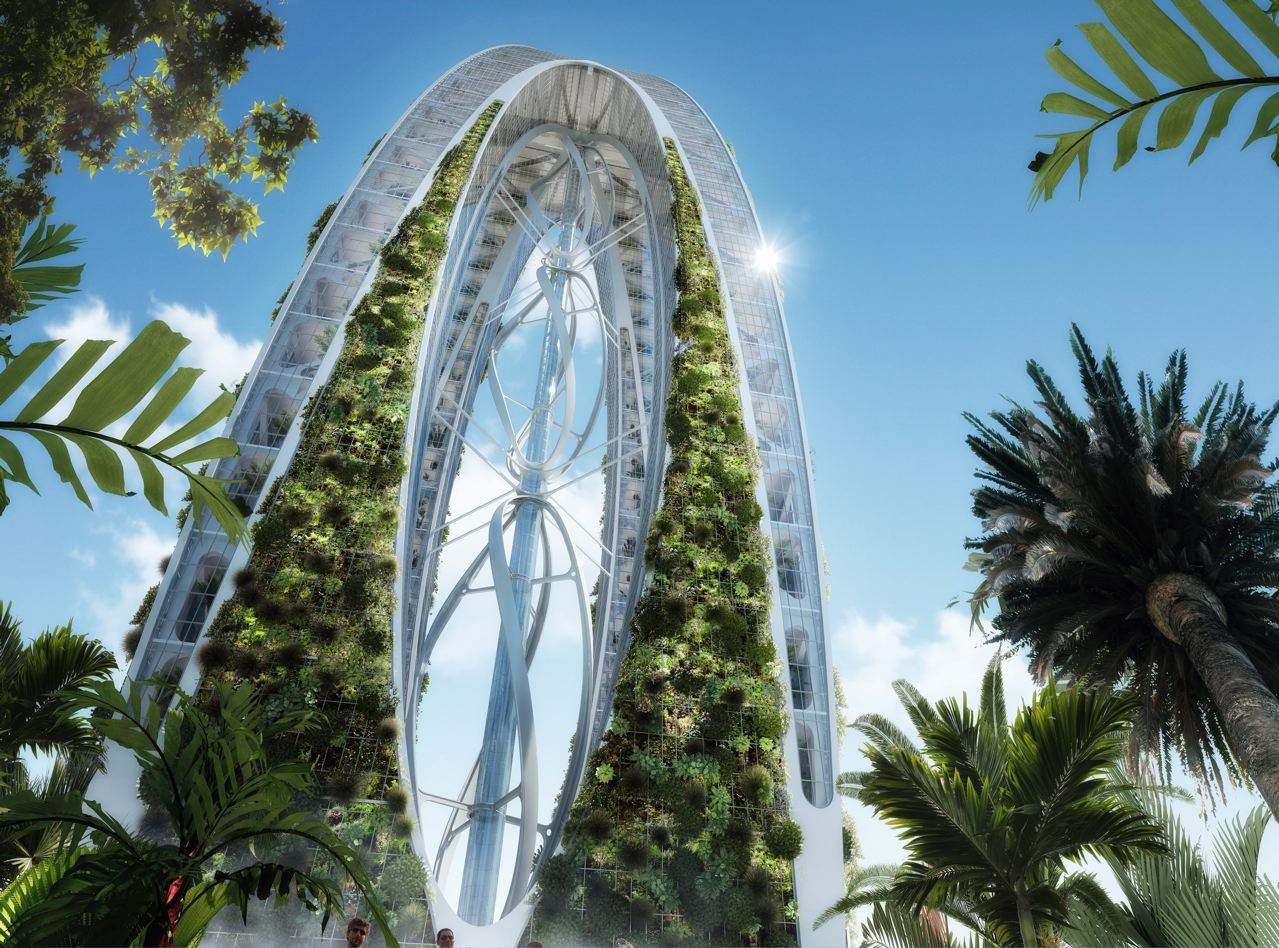

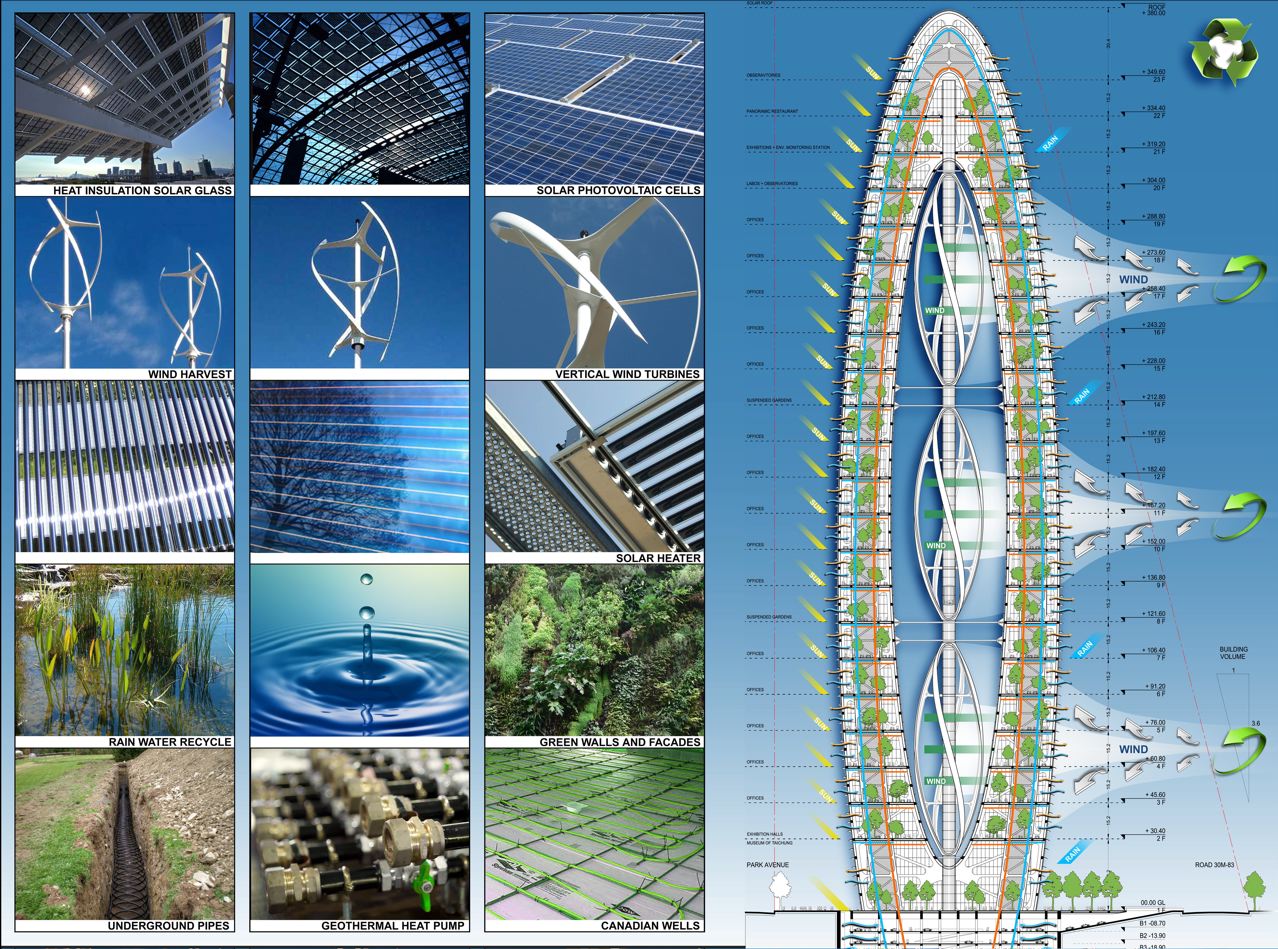

They looked at improvement to the building envelope, the addition of renewable energy and connecting to the smart grid. Key points made showed that, while there may be high initial costs, but there are definite, long-term benefits. And that in order to attain sustainable – meaning GREEN, intelligent, smart, high-performance and net zero – buildings, an integrated design approach using life-cycle costs is required.

The BIPV event at Toronto Harbourfront showed the integration of photovoltaic in the beautiful façade artwork of Sarah Hall. The potential for more BIPV and the challenges of inclusion in the Ontario Power Authority (OPA) feed-in tariff (FIT) program were discussed. As we build and retrofit our buildings and energy grids to be smart, BIPV will be more prevalent.

A report by NanoMarkets, LC, a leading nanotechnology industry market research and analysis firm, entitled BIPV Markets-2011, showed the challenges and complexities for BIPV acceptance given the many different types, costs, and efficiencies.

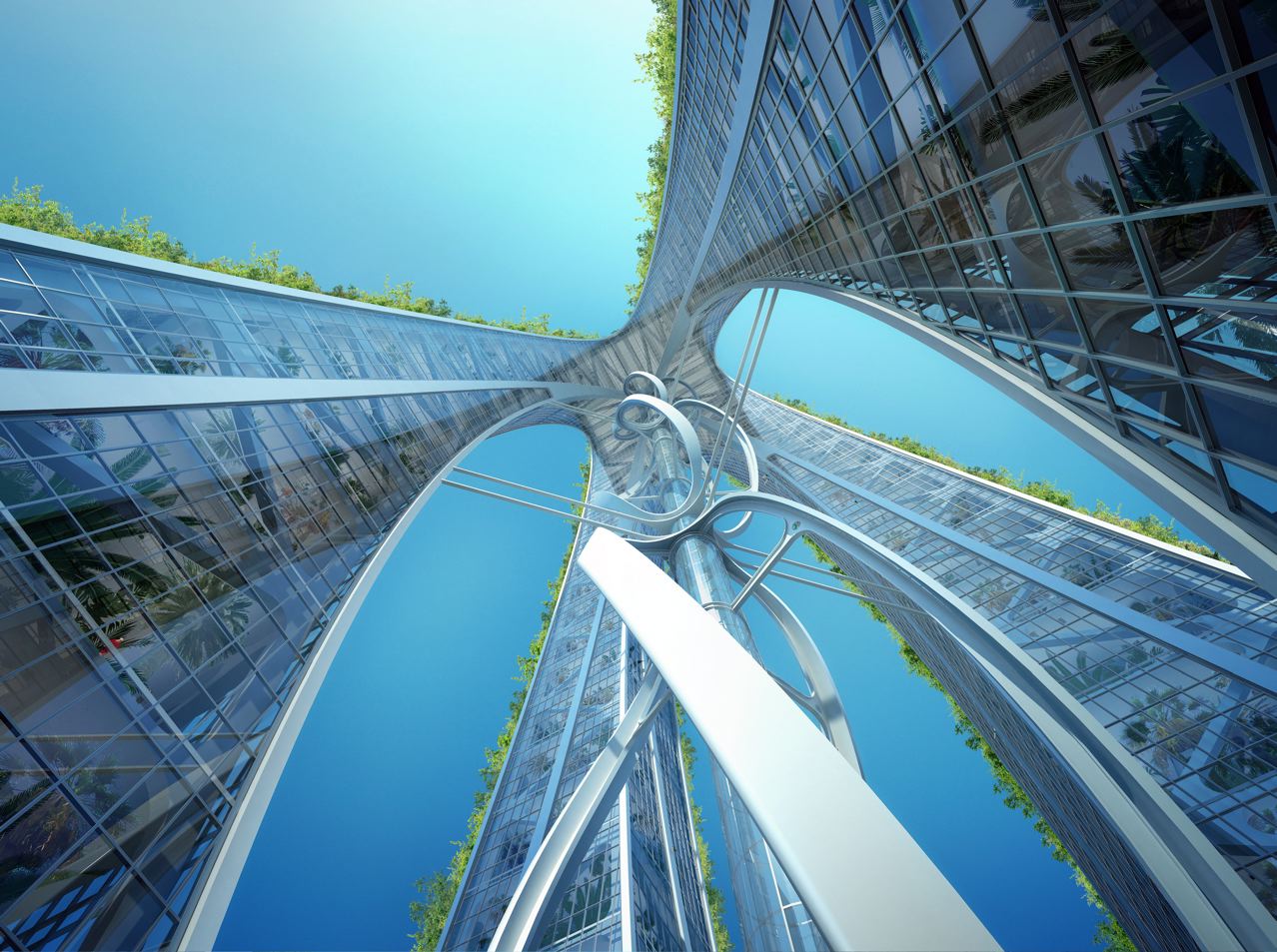

The aesthetic concerns require the BIPV to be part of the building surfaces. The renewable electricity production should be measured, and not wasted, by overcoming inefficiencies in the building, considering its higher costs and possible financial incentives from the utilities and government that are paid for by all energy customers.

As a member of a building-to-grid (B2G) group developing the next smart grid roadmap, I am constantly trying to get the utility experts talking to the building experts so we bring down the silos of the past and develop the future integration of buildings and energy systems.

The smart grid efforts are focused on applying the information technology prevalent in our society today – as part of the electric, gas and water utility infrastructure – so the production, delivery and end use of these utilities will be enhanced and managed in real time. This will lower the rate of the increase in energy and water costs as the utilities replace the antiquated systems that currently have little information capabilities. They must be built to meet growing end-use demand.

At the BES event, a perspective on glazing and the update to the Ontario building code, with the significant energy efficiency requirements, was discussed. And it was timely as recent incidents of falling glazing shows that safety must come first. The event provided presentations on fenestration but it also highlighted the convergence of the energy and building envelope objectives.

One new technology, electronically tintable glass, was presented by Helen Sanders, vice-president at SAGE Electrochromics, Inc. In addition to the examples of facilities that were using the tinting glass to provide shading in real time as the sun moves across the sky, she showed a slide called the ‘Impact of Façade Technologies On Energy Usage in U.S. Building Stock’ from an LBNL report 60049, by Arasteh et al.

This showed the quads of energy use for heating, cooling and lighting for each façade. The most energy used was for the current building stock and average current windows that require the most heating and cooling energy.

It pointed out that less energy is required for low-E films and dynamic and triple pane units. There are significant energy savings in all three energy-usage examples with integrated insulating dynamic façades.

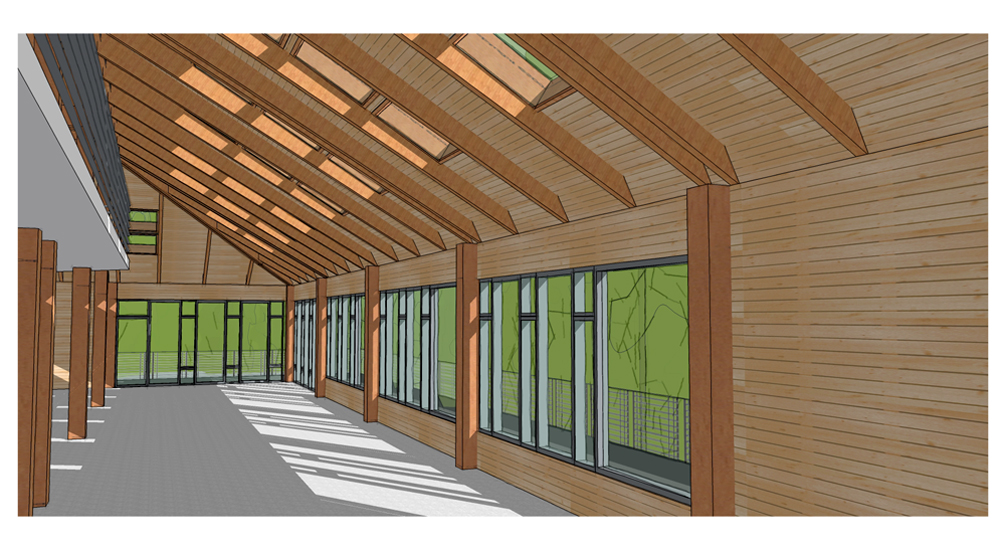

They showed how the technology works. As daylighting is recognized as the contributor to better occupant performance, the integrated building automation system increases natural light, reducing electric lighting, solar gain, glare and cooling while harvesting the daylight when available. It could also provide demand response capabilities when the grid is taxed by air-conditioning load.

Additionally, recent research studies by the Continental Automated Buildings Association (CABA) show that building automation has extended beyond the traditional heating and cooling controls to include the lighting, daylight harvesting, automated shading, and now tintable windows.

CABA’s ‘Bright Green Building’ report showed the convergence of the GREEN and intelligent building rating systems and how they complement each other.

Some of the challenges relate to the owners’ concerns about the perceived additional costs and how to pay for them. It should be noted that while renewable energy currently has higher initial costs, they are fueled by the sun, wind and water at little or no cost and provide environmental benefits.

The higher costs of the innovative building envelope technologies that provide long-term energy savings and production should be evaluated using life-cycle costs. Energy prices are rising. There are utility financial incentives to lower the initial cost and low cost financing available to make “bright” green buildings a reality.

There are many shading and other glazing options. Some are external to the building and they provide excellent opportunity to bring natural light into the building, while also being available to shield the building at times when the solar gain is extreme.

A case in point: Dr. Thanos Tzempelikos, M.A.Sc., Ph.D. recently performed significant energy modelling and produced a study called ‘The impact of Solarmotion-controlled exterior louvers and interior shades on building energy demand for different locations’ for Construction Specialties, Inc.

All in all, with these types of industry events and studies, it’s shown that a sustainable approach requires a life-cycle cost evaluation of all the options from the aesthetics, environmental and smart grid integration benefits.

So let’s have the buildings meet the smart grid and be sustainable.

David Katz is President of Sustainable Resources Management and a former Financial Evaluations Officer at Ontario Hydro where he applied life-cycle costs and multi-attribute scoring to major capital expenditure decisions. He currently consults to building owners and represents sustainable solution technology companies. He can be reached at dkatz@sustainable.on.ca