On July 9, 2017, after nine months of fierce battle, the Iraqi army, backed by an international coalition, defeated the forces of the Islamic State that had occupied Mosul since the proclamation of the “caliphate” in June 2014.

Emerging from the ruins, civilians celebrated the long-awaited liberation of the devastated city from apocalyptic streets and ruined buildings.

A month earlier, on June 19, 2017, Islamic State militants attacked the city’s historic, social, and cultural heritage. Shiite mausoleums and sanctuaries were blown up, as well as the emblematic Al-Nouri mosque and its tilted minaret from the 12th century.

Now, lengthy reconstruction work is ahead for the Iraqi government and the inhabitants. Whole neighborhoods were razed: hospitals, mosques, sports complexes, and thousands of houses. In total, between 50 and 75 per cent of the city was wiped out, leaving only millions of tons of rubble looking for a new life through recycling.

Everything has to be rebuilt. The shovels are clearing the rubble … In the logic of a circular economy and upcycling, everything that can be reused, recycled, and transformed must be inventoried and valued.

A 100-day plan dealt with immediate problems, such as material sorting as well as de-mining, trash removal, and rehabilitation of utility facilities. This process opens the way to a 10-year reconstruction plan, which will affect all Iraqi cities liberated from ISIS. Initial rehabilitation efforts will include roads and bridges, as well as electricity and water services.

According to Iraqi government sources, more than $1-billion will be needed to rehabilitate basic services throughout Mosul and prepare a resilient urban plan to welcome the returning war refugees and internally-displaced persons to the country with dignity.

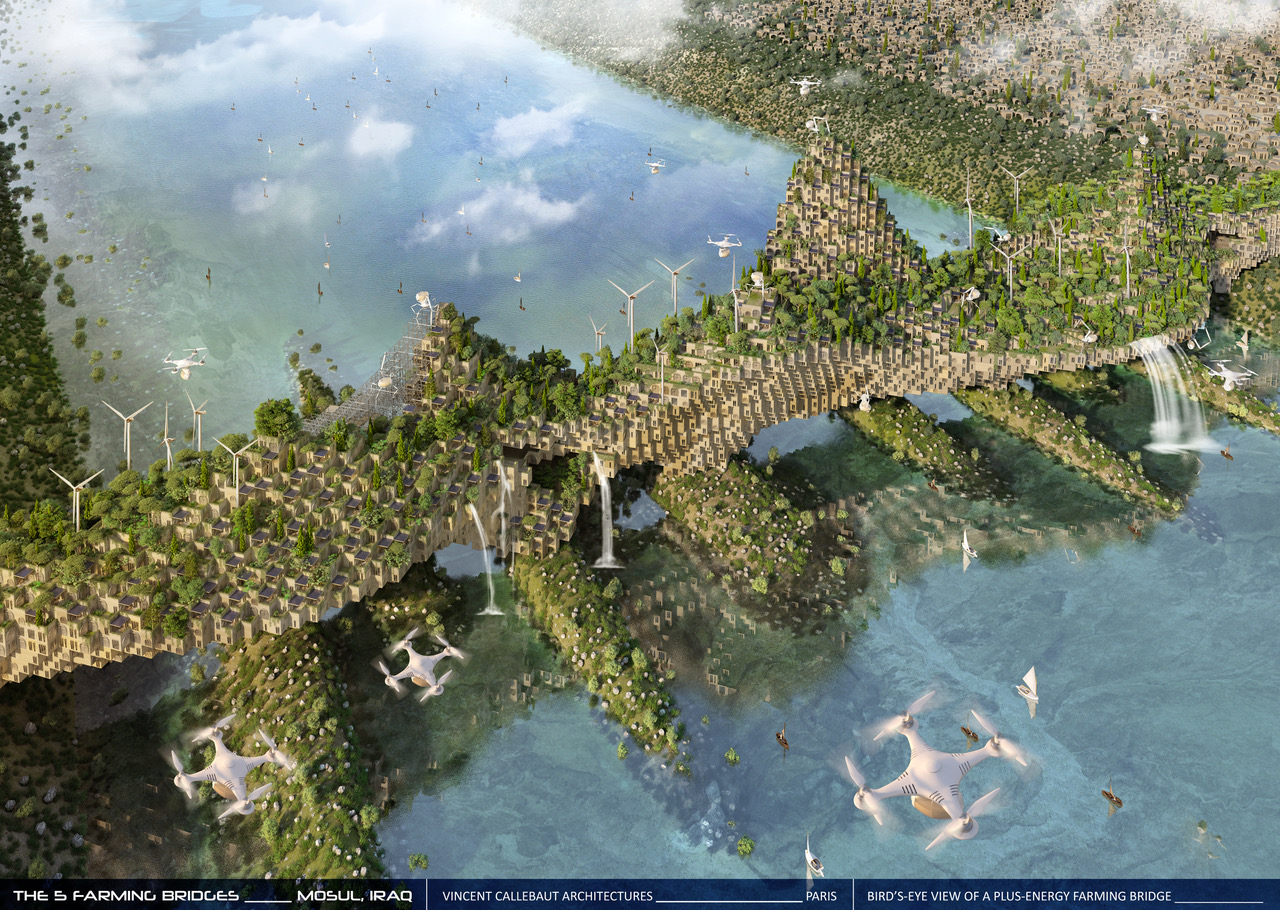

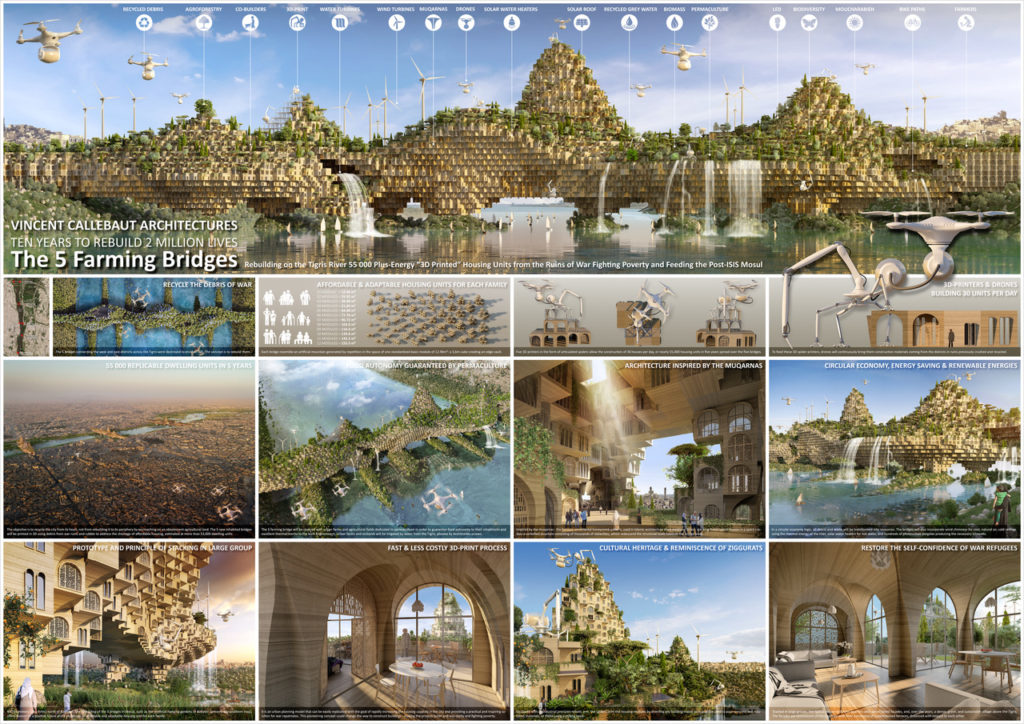

At the heart of the cleanup is the rebuilding of five Mosul bridges connecting the west and east districts across the Tigris which were destroyed. The concept is to rebuild them as inhabited bridges by building the new city over the old city. It is a matter of recycling the city from its heart, not from rebuilding it to its periphery by encroaching on an obsolescent agricultural land.

These inhabited bridges will be printed in 3D using debris from war ruins and rubble to address the shortage of affordable housing, estimated at more than 53,000 dwelling units.

They will be covered with urban farms and agricultural fields dedicated to permaculture in order to guarantee food autonomy to their inhabitants and excellent thermal inertia to the built environment. Urban farms and orchards will be irrigated by water from the Tigris, pumped by Archimedes screws. Gray water from bathrooms and kitchens will also be recycled and filtered by plants in lagoon waterfalls connected with the river. Biomass composters will feed their orchards and vegetable gardens suspended in biological fertilizers.

The bridges will also incorporate wind chimneys for cool, natural air, cold ceilings using the thermal energy of the river, solar water heaters for hot water, and hundreds of photovoltaic pergolas producing the necessary kilowatts.

In architectural terms, each bridge will resemble an artificial mountain generated by repetition in the space of one single basic module of 12.96m²: a 3,6m cube creating an edge vault using the intersection of two cradles, which intersect at right angles.

Inspired by the muqarnas – the famous ornamental honeycomb pattern used in Islamic architecture since medieval times – stacking these typical houses in a space creates a corbelled structure consisting of thousands of stalactites, which redescend the structural loads towards the bridge piers.

The typical houses will consist of two, five or 10 modules, respectively, forming dwellings of 25, 65, and 120 m². The constructive system will thus respond to different habitable capacity requirements, according to the size of the Iraqi family to be accommodated. Stacked in large groups, the typical houses will form quarters with ocher-toned facades, and, over the years, a dense, green, and sustainable village above the Tigris. The facades are reminiscent of the ziggurats with their succession of superimposed terraces, distanced with respect to each other.

Five 3D printers in the form of articulated spiders will allow the construction of 30 houses per day, or nearly 55,000 housing units in five years spread over the five bridges.

All debris will be transformed into resources. To feed these 3D spider printers, drones will continuously bring them construction materials coming from the districts in ruins; previously crushed and transformed in recycling centers. Equipped with an industrial precision robotic arm, the spiders print the housing modules by directing any building nozzle such as those used to pour concrete and insulation materials, or those using a milling head.

What kind of impact are we talking about? In 10 years, two-million lives are expected to be positively affected.

Restoring the self-confidence of war refugees, their confidence in an optimistic future, and allowing them to participate actively in the repatriation process, is essential to the success of this reconstruction in the heart of the city.

Mosul, about 400 kilometres north of Baghdad, will be a showcase with the rebuilding of the five bridges, harkening back to the mythical hanging gardens of Babylon (present-day southern Iraq), offering a vision of a positive future and a prototype of affordable and adaptable housing for each family unit.

It is an urban planning model that can be easily replicated with the goal of rapidly increasing the housing capacity in the city and providing a practical and inspiring solution for war repatriates. This pioneering concept could change the way to construct buildings – making the process faster and less costly, fighting poverty and feeding the post-ISIS Mosul.

The 5 Farming Bridges is the Winning Project of the Rifat Chadirji Prize Competition (3rd Place) – “Rebuilding Iraq’s Liberated Areas: Mosul’s Housing”

Copyright / Vincent Callebaut Architectures