News that a four-storey, 40,000-square-foot multi-tenant medical office building, planned for construction in Stouffville, Ontario, will seek certification through the BRE Environmental Assessment Method (BREEAM) marks a milestone for the international standard.

Established 21 years ago by the Building Research Establishment (BRE) as a tool to measure the sustainability of new buildings, BREEAM measures the sustainability of the built environment using local knowledge and standards and has been a mainstay in the United Kingdom. However, green building proponents have adapted and adopted it in various forms around the world.

BREEAM is widely credited with inspiring Green Star in Australia, Haute Qualité Environnementale (High Environmental Quality, or HQE) in France, and Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) in North America, among many others.

There are key similarities and differences between BREEAM and LEED. BREEAM certifications range from Pass to Outstanding, while LEED’s range from Basic to Platinum. BREEAM trains assessors to evaluate completed projects, which are then checked by BRE. BRE then then issues certifications when warranted. LEED, meanwhile, operates through national green building councils, and their assessors evaluate projects.

BREEAM director Martin Townsend says his organization currently lists more than a million buildings as assessed or registered.

“Our key objective is to build buildings that people want to live and work in, as well great communities to live, whilst improving the performance, functionality, flexibility and durability of the building itself,” he says.

Operated by an independent board representing industry stakeholders under the wider governance of BRE Trust, a not for profit organisation, BRE Global is looking to further involve international experts and the global BREEAM community.

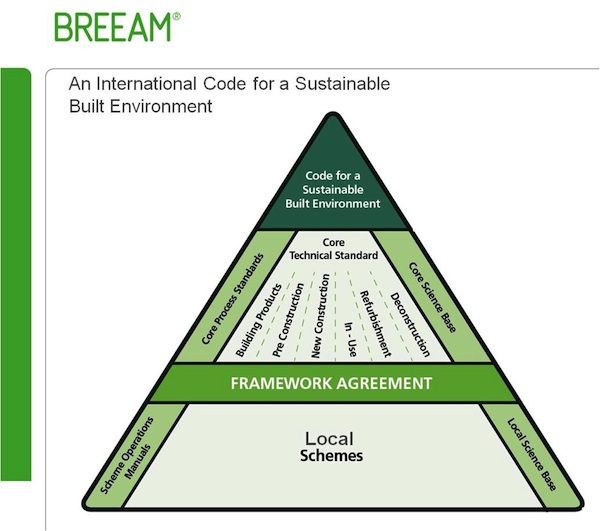

“I see BREEAM as a movement for sustainable development, with local schemes, processes, science and governance cooperating internationally under an overarching framework defined by core standards, core science and metrics” Townsend says.

He adds that BRE Global is currently seeking nominations for experts from countries such as Canada to join its Standing Panel for Peer Review and to participate in regular BREEAM Conferences on research and practice.

“We hope, as we develop our network in Canada, that experts will come forward so that they can also play an active role in ensuring that the tools and standard are the correct ones to drive the improved performance of new communities, buildings as well. If we are to quicken the debate about building better buildings we need to do so by sharing our knowledge and experience.”

Townsend adds that BRE Global hopes the Canadian market will integrate its own data on the actual performance of existing buildings into the work it is undertaking with the International Sustainability Alliance (ISA). ISA was launched at Expo Real in Munich in 2009, and its membership represents an estimated $196 billion in real estate ownership and management, according to Townsend.

“BREEAM is ultimately a tool through which sustainability goals can be measured and improved on an international level,” he says.

“Up until this point, although many of us have wished to improve the buildings we live and work in, we have felt inhibited by the financial implications,” Townsend says. “The environment and the economy have long been pitted against one another, and many feel that they must choose between their pocket or the planet. BREEAM offers a realistic, cost-effective solution to this and supports the notion that these old sparring partners need not do battle after all.”

For more information about BREEAM please visit www.breeam.org.

By Saul Chernos