By GREG McMILLAN

You couldn’t say that Rafael Schmidt and his team from Zurich-based architecture and design studio RAFAA didn’t give it the old college try.

But, alas, their project, called the Solar City Tower, is not expected to see the light of day when the 2016 Rio Olympic Games roll around.

They had hoped, when entering an international concept design competition back in 2010, that the project would serve as a symbolic tower that would help make the Olympics more sustainable and become a lightning rod for the global green movement.

However, as Schmidt told Green Building and Sustainable Strategies magazine, the project – which would have created renewable energy for use in the city of Rio as well as the Olympic Village – is unlikely to proceed after facing a litany of unforeseen problems.

“We ended up facing different technical, organizational and environmental problems,” Schmidt says.

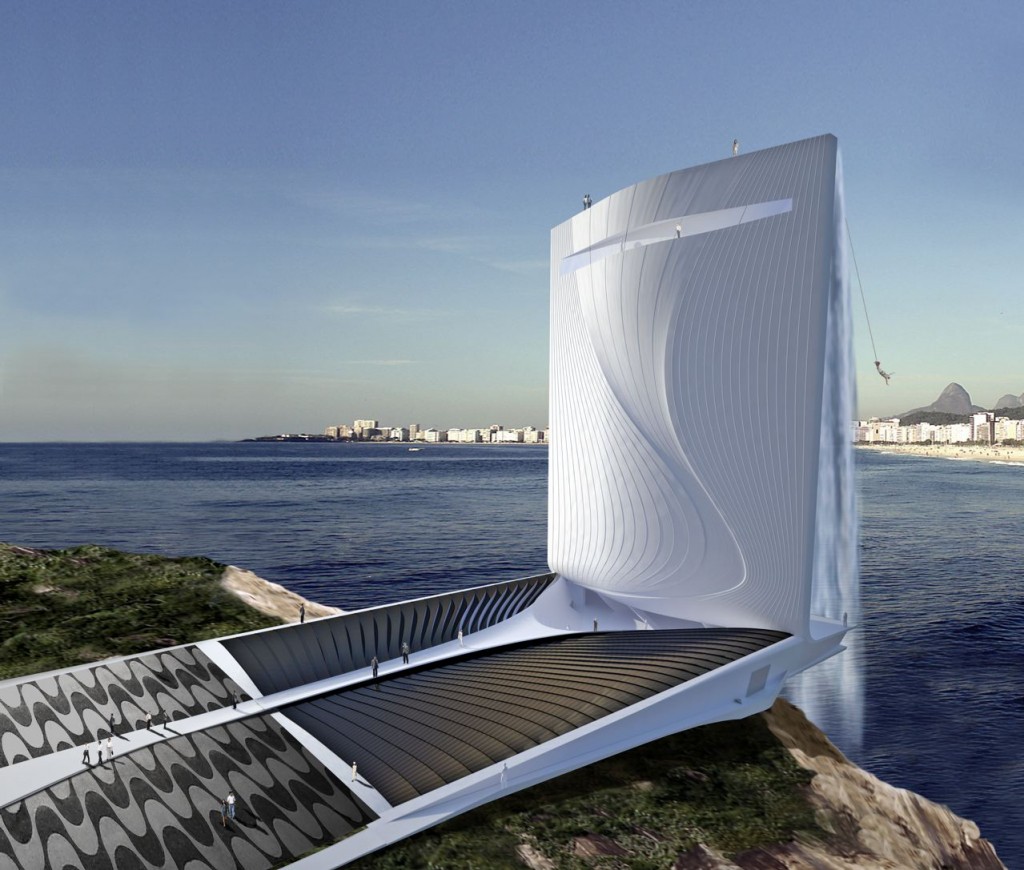

Not difficult to imagine, actually, considering the scope of the original design. RAFAA placed the project on the island of Cotonduba, in Rio’s bay. It featured a massive solar system to generate daytime-power, plus a turbines-pumped water storage system (including a waterfall) to continue to provide nighttime-power.

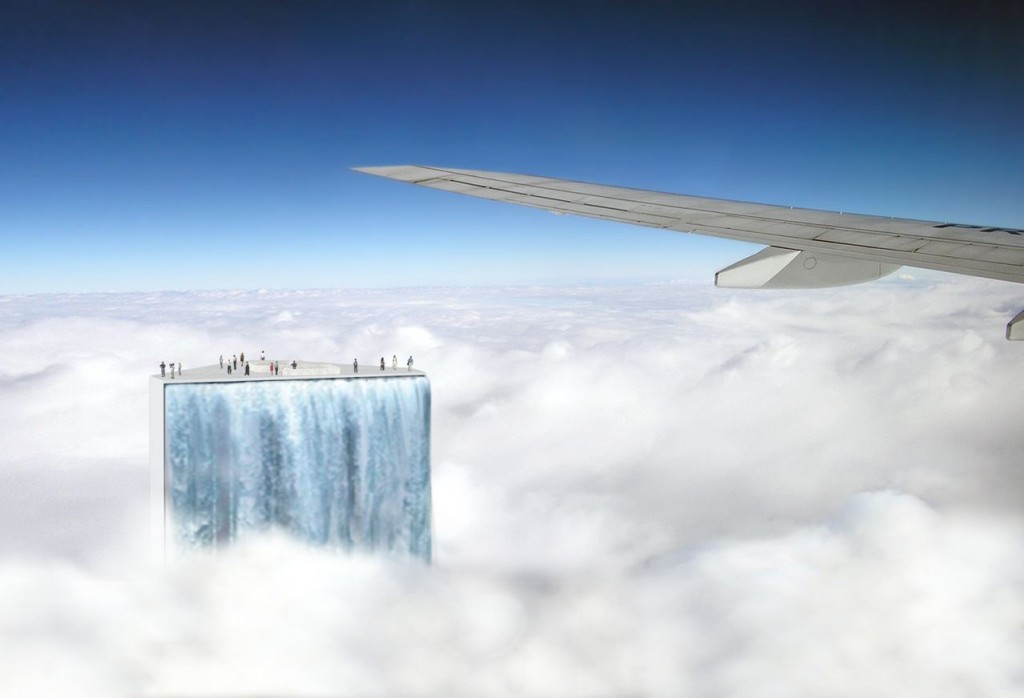

The resulting structure was supposed to create a riveting image for all those arriving at the Olympics, either by air or sea.

But it would also have a utilitarian use, with both entrance and amphitheatre areas serving as places for social gatherings and other events. The public could access the facility and a cafeteria and shopping area were positioned underneath the waterfall to serve up a breathtaking view.

Elevators were in place to take visitors up to observation decks and an urban balcony, situated 105 metres above sea level. There was even a retractable platform in the design, where visitors could participate in bungee jumping.

So, that was the original concept put forth by RAFAA. Then reality set in.

The first stumbling block, explains Schmidt, came when UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) informed RAFAA that the area around Cotunduba Island had been designated as a World Heritage site. And UNESCO does all it can do to protect and conserve such properties.

And then there were technical flaws in the design that were pointed out to RAFAA.

“The solar panels we had in place only would produce about eight watts per square foot, so the size of the solar field to achieve our zero carbon footprint ideal would be 10 times the size of the island,” Schmidt says. “Therefore, the cost of the solar field would consume the majority of the project budget.”

He says it was determined that the salt spray and residue from the Atlantic Ocean would decrease the solar panels’ efficiency significantly – “ Not to mention the corrosion of all copper wires that connect the panels.”

The island location would have sent costs skyrocketing, as well, just by running electrical lines to the mainland, he says.

“Also, the energy needed to pump water to the top of the waterfall would have exceeded the turbines-generated power produced,” he says.

Despite the setbacks, Schmidt is convinced that, on some level, the idea of the Solar City Tower, has been a success.

“It shows the real challenges for the imminent post-oil era,” he says. “The project represents a message of a society facing a future, thus it is the representation of an inner attitude and awareness.”